#!/usr/bin/env python

# coding: utf-8

# Credits: Forked from [deep-learning-keras-tensorflow](https://github.com/leriomaggio/deep-learning-keras-tensorflow) by Valerio Maggio

# # Convolutional Neural Network

# ### References:

#

# Some of the images and the content I used came from this great couple of blog posts \[1\] [https://adeshpande3.github.io/adeshpande3.github.io/]() and \[2\] the terrific book, ["Neural Networks and Deep Learning"](http://neuralnetworksanddeeplearning.com/) by Michael Nielsen. (**Strongly recommend**)

# A convolutional neural network (CNN, or ConvNet) is a type of **feed-forward** artificial neural network in which the connectivity pattern between its neurons is inspired by the organization of the animal visual cortex.

# The networks consist of multiple layers of small neuron collections which process portions of the input image, called **receptive fields**.

#

# The outputs of these collections are then tiled so that their input regions overlap, to obtain a _better representation_ of the original image; this is repeated for every such layer.

# ## How does it look like?

#  #

# > source: https://flickrcode.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/conv-net2.png

# # The Problem Space

#

# ## Image Classification

# Image classification is the task of taking an input image and outputting a class (a cat, dog, etc) or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# For humans, this task of recognition is one of the first skills we learn from the moment we are born and is one that comes naturally and effortlessly as adults.

# These skills of being able to quickly recognize patterns, *generalize* from prior knowledge, and adapt to different image environments are ones that we do not share with machines.

# ## Inputs and Outputs

#

#

# > source: https://flickrcode.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/conv-net2.png

# # The Problem Space

#

# ## Image Classification

# Image classification is the task of taking an input image and outputting a class (a cat, dog, etc) or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# For humans, this task of recognition is one of the first skills we learn from the moment we are born and is one that comes naturally and effortlessly as adults.

# These skills of being able to quickly recognize patterns, *generalize* from prior knowledge, and adapt to different image environments are ones that we do not share with machines.

# ## Inputs and Outputs

#  #

# source: [http://www.pawbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/551/2014/11/corgi-puppies-21.jpg]()

# When a computer sees an image (takes an image as input), it will see an array of pixel values.

#

# Depending on the resolution and size of the image, it will see a 32 x 32 x 3 array of numbers (The 3 refers to RGB values).

#

# let's say we have a color image in JPG form and its size is 480 x 480. The representative array will be 480 x 480 x 3. Each of these numbers is given a value from 0 to 255 which describes the pixel intensity at that point.

# ## Goal

# What we want the computer to do is to be able to differentiate between all the images it’s given and figure out the unique features that make a dog a dog or that make a cat a cat.

# When we look at a picture of a dog, we can classify it as such if the picture has identifiable features such as paws or 4 legs.

#

# In a similar way, the computer should be able to perform image classification by looking for *low level* features such as edges and curves, and then building up to more abstract concepts through a series of **convolutional layers**.

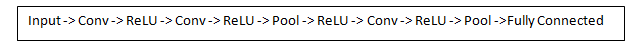

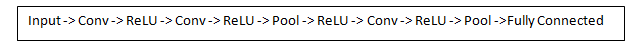

# ## Structure of a CNN

# > A more detailed overview of what CNNs do would be that you take the image, pass it through a series of convolutional, nonlinear, pooling (downsampling), and fully connected layers, and get an output. As we said earlier, the output can be a single class or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# source: [1]

# # Convolutional Layer

# The first layer in a CNN is always a **Convolutional Layer**.

#

#

#

# source: [http://www.pawbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/551/2014/11/corgi-puppies-21.jpg]()

# When a computer sees an image (takes an image as input), it will see an array of pixel values.

#

# Depending on the resolution and size of the image, it will see a 32 x 32 x 3 array of numbers (The 3 refers to RGB values).

#

# let's say we have a color image in JPG form and its size is 480 x 480. The representative array will be 480 x 480 x 3. Each of these numbers is given a value from 0 to 255 which describes the pixel intensity at that point.

# ## Goal

# What we want the computer to do is to be able to differentiate between all the images it’s given and figure out the unique features that make a dog a dog or that make a cat a cat.

# When we look at a picture of a dog, we can classify it as such if the picture has identifiable features such as paws or 4 legs.

#

# In a similar way, the computer should be able to perform image classification by looking for *low level* features such as edges and curves, and then building up to more abstract concepts through a series of **convolutional layers**.

# ## Structure of a CNN

# > A more detailed overview of what CNNs do would be that you take the image, pass it through a series of convolutional, nonlinear, pooling (downsampling), and fully connected layers, and get an output. As we said earlier, the output can be a single class or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# source: [1]

# # Convolutional Layer

# The first layer in a CNN is always a **Convolutional Layer**.

#

#  # ### Convolutional filters

#

#

# A Convolutional Filter much like a **kernel** in image recognition is a small matrix useful for blurring, sharpening, embossing, edge detection, and more.

#

# This is accomplished by means of convolution between a kernel and an image.

#

# The main difference _here_ is that the conv matrices are **learned**.

#

# ### Convolutional filters

#

#

# A Convolutional Filter much like a **kernel** in image recognition is a small matrix useful for blurring, sharpening, embossing, edge detection, and more.

#

# This is accomplished by means of convolution between a kernel and an image.

#

# The main difference _here_ is that the conv matrices are **learned**.

#  # As the filter is sliding, or **convolving**, around the input image, it is multiplying the values in the filter with the original pixel values of the image (aka computing **element wise multiplications**).

#

# As the filter is sliding, or **convolving**, around the input image, it is multiplying the values in the filter with the original pixel values of the image (aka computing **element wise multiplications**).

#  # iNow, we repeat this process for every location on the input volume. (Next step would be moving the filter to the right by 1 unit, then right again by 1, and so on).

# After sliding the filter over all the locations, we are left with an array of numbers usually called an **activation map** or **feature map**.

# ## High Level Perspective

#

# Let’s talk about briefly what this convolution is actually doing from a high level.

# Each of these filters can be thought of as **feature identifiers** (e.g. *straight edges, simple colors, curves*)

#

# iNow, we repeat this process for every location on the input volume. (Next step would be moving the filter to the right by 1 unit, then right again by 1, and so on).

# After sliding the filter over all the locations, we are left with an array of numbers usually called an **activation map** or **feature map**.

# ## High Level Perspective

#

# Let’s talk about briefly what this convolution is actually doing from a high level.

# Each of these filters can be thought of as **feature identifiers** (e.g. *straight edges, simple colors, curves*)

#  # ### Visualisation of the Receptive Field

#

# ### Visualisation of the Receptive Field

#  #

#  #

#  # The value is much lower! This is because there wasn’t anything in the image section that responded to the curve detector filter. Remember, the output of this conv layer is an activation map.

#

# # Going Deeper Through the Network

# Now in a traditional **convolutional neural network** architecture, there are other layers that are interspersed between these conv layers.

#

#

# The value is much lower! This is because there wasn’t anything in the image section that responded to the curve detector filter. Remember, the output of this conv layer is an activation map.

#

# # Going Deeper Through the Network

# Now in a traditional **convolutional neural network** architecture, there are other layers that are interspersed between these conv layers.

#

#  # ## ReLU (Rectified Linear Units) Layer

# After each conv layer, it is convention to apply a *nonlinear layer* (or **activation layer**) immediately afterward.

#

#

# The purpose of this layer is to introduce nonlinearity to a system that basically has just been computing linear operations during the conv layers (just element wise multiplications and summations)

# In the past, nonlinear functions like tanh and sigmoid were used, but researchers found out that **ReLU layers** work far better because the network is able to train a lot faster (because of the computational efficiency) without making a significant difference to the accuracy.

# It also helps to alleviate the **vanishing gradient problem**, which is the issue where the lower layers of the network train very slowly because the gradient decreases exponentially through the layers

# (**very briefly**)

#

# Vanishing gradient problem depends on the choice of the activation function.

#

# Many common activation functions (e.g `sigmoid` or `tanh`) *squash* their input into a very small output range in a very non-linear fashion.

#

# For example, sigmoid maps the real number line onto a "small" range of [0, 1].

# As a result, there are large regions of the input space which are mapped to an extremely small range.

#

# In these regions of the input space, even a large change in the input will produce a small change in the output - hence the **gradient is small**.

# ### ReLu

#

# The **ReLu** function is defined as $f(x) = \max(0, x),$ [2]

#

# A smooth approximation to the rectifier is the *analytic function*: $f(x) = \ln(1 + e^x)$

#

# which is called the **softplus** function.

#

# The derivative of softplus is $f'(x) = e^x / (e^x + 1) = 1 / (1 + e^{-x})$, i.e. the **logistic function**.

#

# [2] [http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~fritz/absps/reluICML.pdf]() by G. E. Hinton

# ## Pooling Layers

# After some ReLU layers, it is customary to apply a **pooling layer** (aka *downsampling layer*).

# In this category, there are also several layer options, with **maxpooling** being the most popular.

# Example of a MaxPooling filter

#

# ## ReLU (Rectified Linear Units) Layer

# After each conv layer, it is convention to apply a *nonlinear layer* (or **activation layer**) immediately afterward.

#

#

# The purpose of this layer is to introduce nonlinearity to a system that basically has just been computing linear operations during the conv layers (just element wise multiplications and summations)

# In the past, nonlinear functions like tanh and sigmoid were used, but researchers found out that **ReLU layers** work far better because the network is able to train a lot faster (because of the computational efficiency) without making a significant difference to the accuracy.

# It also helps to alleviate the **vanishing gradient problem**, which is the issue where the lower layers of the network train very slowly because the gradient decreases exponentially through the layers

# (**very briefly**)

#

# Vanishing gradient problem depends on the choice of the activation function.

#

# Many common activation functions (e.g `sigmoid` or `tanh`) *squash* their input into a very small output range in a very non-linear fashion.

#

# For example, sigmoid maps the real number line onto a "small" range of [0, 1].

# As a result, there are large regions of the input space which are mapped to an extremely small range.

#

# In these regions of the input space, even a large change in the input will produce a small change in the output - hence the **gradient is small**.

# ### ReLu

#

# The **ReLu** function is defined as $f(x) = \max(0, x),$ [2]

#

# A smooth approximation to the rectifier is the *analytic function*: $f(x) = \ln(1 + e^x)$

#

# which is called the **softplus** function.

#

# The derivative of softplus is $f'(x) = e^x / (e^x + 1) = 1 / (1 + e^{-x})$, i.e. the **logistic function**.

#

# [2] [http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~fritz/absps/reluICML.pdf]() by G. E. Hinton

# ## Pooling Layers

# After some ReLU layers, it is customary to apply a **pooling layer** (aka *downsampling layer*).

# In this category, there are also several layer options, with **maxpooling** being the most popular.

# Example of a MaxPooling filter

#  # Other options for pooling layers are average pooling and L2-norm pooling.

# The intuition behind this Pooling layer is that once we know that a specific feature is in the original input volume (there will be a high activation value), its exact location is not as important as its relative location to the other features.

#

# Therefore this layer drastically reduces the spatial dimension (the length and the width but not the depth) of the input volume.

#

# This serves two main purposes: reduce the amount of parameters; controlling overfitting.

# An intuitive explanation for the usefulness of pooling could be explained by an example:

#

# Lets assume that we have a filter that is used for detecting faces. The exact pixel location of the face is less relevant then the fact that there is a face "somewhere at the top"

# ## Dropout Layer

# The **dropout layers** have the very specific function to *drop out* a random set of activations in that layers by setting them to zero in the forward pass. Simple as that.

#

# It allows to avoid *overfitting* but has to be used **only** at training time and **not** at test time.

# ## Fully Connected Layer

# The last layer, however, is an important one, namely the **Fully Connected Layer**.

# Basically, a FC layer looks at what high level features most strongly correlate to a particular class and has particular weights so that when you compute the products between the weights and the previous layer, you get the correct probabilities for the different classes.

#

# Other options for pooling layers are average pooling and L2-norm pooling.

# The intuition behind this Pooling layer is that once we know that a specific feature is in the original input volume (there will be a high activation value), its exact location is not as important as its relative location to the other features.

#

# Therefore this layer drastically reduces the spatial dimension (the length and the width but not the depth) of the input volume.

#

# This serves two main purposes: reduce the amount of parameters; controlling overfitting.

# An intuitive explanation for the usefulness of pooling could be explained by an example:

#

# Lets assume that we have a filter that is used for detecting faces. The exact pixel location of the face is less relevant then the fact that there is a face "somewhere at the top"

# ## Dropout Layer

# The **dropout layers** have the very specific function to *drop out* a random set of activations in that layers by setting them to zero in the forward pass. Simple as that.

#

# It allows to avoid *overfitting* but has to be used **only** at training time and **not** at test time.

# ## Fully Connected Layer

# The last layer, however, is an important one, namely the **Fully Connected Layer**.

# Basically, a FC layer looks at what high level features most strongly correlate to a particular class and has particular weights so that when you compute the products between the weights and the previous layer, you get the correct probabilities for the different classes.

#  # # CNN in Keras

# **Keras** supports:

#

# - 1D Convolutional Layers;

# - 2D Convolutional Layers;

# - 3D Convolutional Layers;

#

# The corresponding `keras` package is `keras.layers.convolutional`

# #### Convolution1D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution1D

# Convolution1D(nb_filter, filter_length, init='uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample_length=1,

# W_regularizer=None, b_regularizer=None,

# activity_regularizer=None, W_constraint=None,

# b_constraint=None, bias=True, input_dim=None,

# input_length=None)

# ```

# >Convolution operator for filtering neighborhoods of **one-dimensional inputs**. When using this layer as the first layer in a model, either provide the keyword argument `input_dim` (int, e.g. 128 for sequences of 128-dimensional vectors), or `input_shape` (tuple of integers, e.g. (10, 128) for sequences of 10 vectors of 128-dimensional vectors).

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a convolution 1d of length 3 to a sequence with 10 timesteps,

# # with 64 output filters

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution1D(64, 3, border_mode='same', input_shape=(10, 32)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 64)

#

# # add a new conv1d on top

# model.add(Convolution1D(32, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 32)

# ```

# #### Convolution2D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution2D

# Convolution2D(nb_filter, nb_row, nb_col,

# init='glorot_uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample=(1, 1),

# dim_ordering='default', W_regularizer=None,

# b_regularizer=None, activity_regularizer=None,

# W_constraint=None, b_constraint=None,

# bias=True)

# ```

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a 3x3 convolution with 64 output filters on a 256x256 image:

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution2D(64, 3, 3, border_mode='same',

# input_shape=(3, 256, 256)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 64, 256, 256)

#

# # add a 3x3 convolution on top, with 32 output filters:

# model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 32, 256, 256)

#

# ```

# ## Dimensions of Conv filters in Keras

# The complex structure of ConvNets *may* lead to a representation that is challenging to understand.

# Of course, the dimensions vary according to the dimension of the Convolutional filters (e.g. 1D, 2D)

# ### Convolution1D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `steps`, `input_dim`).

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `new_steps`, `nb_filter`).

# ### Convolution2D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `channels`, `rows`, `cols`) if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `rows`, `cols`, `channels`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `nb_filter`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`)

# if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`, `nb_filter`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

# # CNN in Keras

# **Keras** supports:

#

# - 1D Convolutional Layers;

# - 2D Convolutional Layers;

# - 3D Convolutional Layers;

#

# The corresponding `keras` package is `keras.layers.convolutional`

# #### Convolution1D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution1D

# Convolution1D(nb_filter, filter_length, init='uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample_length=1,

# W_regularizer=None, b_regularizer=None,

# activity_regularizer=None, W_constraint=None,

# b_constraint=None, bias=True, input_dim=None,

# input_length=None)

# ```

# >Convolution operator for filtering neighborhoods of **one-dimensional inputs**. When using this layer as the first layer in a model, either provide the keyword argument `input_dim` (int, e.g. 128 for sequences of 128-dimensional vectors), or `input_shape` (tuple of integers, e.g. (10, 128) for sequences of 10 vectors of 128-dimensional vectors).

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a convolution 1d of length 3 to a sequence with 10 timesteps,

# # with 64 output filters

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution1D(64, 3, border_mode='same', input_shape=(10, 32)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 64)

#

# # add a new conv1d on top

# model.add(Convolution1D(32, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 32)

# ```

# #### Convolution2D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution2D

# Convolution2D(nb_filter, nb_row, nb_col,

# init='glorot_uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample=(1, 1),

# dim_ordering='default', W_regularizer=None,

# b_regularizer=None, activity_regularizer=None,

# W_constraint=None, b_constraint=None,

# bias=True)

# ```

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a 3x3 convolution with 64 output filters on a 256x256 image:

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution2D(64, 3, 3, border_mode='same',

# input_shape=(3, 256, 256)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 64, 256, 256)

#

# # add a 3x3 convolution on top, with 32 output filters:

# model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 32, 256, 256)

#

# ```

# ## Dimensions of Conv filters in Keras

# The complex structure of ConvNets *may* lead to a representation that is challenging to understand.

# Of course, the dimensions vary according to the dimension of the Convolutional filters (e.g. 1D, 2D)

# ### Convolution1D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `steps`, `input_dim`).

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `new_steps`, `nb_filter`).

# ### Convolution2D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `channels`, `rows`, `cols`) if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `rows`, `cols`, `channels`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `nb_filter`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`)

# if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`, `nb_filter`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

#

# > source: https://flickrcode.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/conv-net2.png

# # The Problem Space

#

# ## Image Classification

# Image classification is the task of taking an input image and outputting a class (a cat, dog, etc) or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# For humans, this task of recognition is one of the first skills we learn from the moment we are born and is one that comes naturally and effortlessly as adults.

# These skills of being able to quickly recognize patterns, *generalize* from prior knowledge, and adapt to different image environments are ones that we do not share with machines.

# ## Inputs and Outputs

#

#

# > source: https://flickrcode.files.wordpress.com/2014/10/conv-net2.png

# # The Problem Space

#

# ## Image Classification

# Image classification is the task of taking an input image and outputting a class (a cat, dog, etc) or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# For humans, this task of recognition is one of the first skills we learn from the moment we are born and is one that comes naturally and effortlessly as adults.

# These skills of being able to quickly recognize patterns, *generalize* from prior knowledge, and adapt to different image environments are ones that we do not share with machines.

# ## Inputs and Outputs

#  #

# source: [http://www.pawbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/551/2014/11/corgi-puppies-21.jpg]()

# When a computer sees an image (takes an image as input), it will see an array of pixel values.

#

# Depending on the resolution and size of the image, it will see a 32 x 32 x 3 array of numbers (The 3 refers to RGB values).

#

# let's say we have a color image in JPG form and its size is 480 x 480. The representative array will be 480 x 480 x 3. Each of these numbers is given a value from 0 to 255 which describes the pixel intensity at that point.

# ## Goal

# What we want the computer to do is to be able to differentiate between all the images it’s given and figure out the unique features that make a dog a dog or that make a cat a cat.

# When we look at a picture of a dog, we can classify it as such if the picture has identifiable features such as paws or 4 legs.

#

# In a similar way, the computer should be able to perform image classification by looking for *low level* features such as edges and curves, and then building up to more abstract concepts through a series of **convolutional layers**.

# ## Structure of a CNN

# > A more detailed overview of what CNNs do would be that you take the image, pass it through a series of convolutional, nonlinear, pooling (downsampling), and fully connected layers, and get an output. As we said earlier, the output can be a single class or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# source: [1]

# # Convolutional Layer

# The first layer in a CNN is always a **Convolutional Layer**.

#

#

#

# source: [http://www.pawbuzz.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/551/2014/11/corgi-puppies-21.jpg]()

# When a computer sees an image (takes an image as input), it will see an array of pixel values.

#

# Depending on the resolution and size of the image, it will see a 32 x 32 x 3 array of numbers (The 3 refers to RGB values).

#

# let's say we have a color image in JPG form and its size is 480 x 480. The representative array will be 480 x 480 x 3. Each of these numbers is given a value from 0 to 255 which describes the pixel intensity at that point.

# ## Goal

# What we want the computer to do is to be able to differentiate between all the images it’s given and figure out the unique features that make a dog a dog or that make a cat a cat.

# When we look at a picture of a dog, we can classify it as such if the picture has identifiable features such as paws or 4 legs.

#

# In a similar way, the computer should be able to perform image classification by looking for *low level* features such as edges and curves, and then building up to more abstract concepts through a series of **convolutional layers**.

# ## Structure of a CNN

# > A more detailed overview of what CNNs do would be that you take the image, pass it through a series of convolutional, nonlinear, pooling (downsampling), and fully connected layers, and get an output. As we said earlier, the output can be a single class or a probability of classes that best describes the image.

#

# source: [1]

# # Convolutional Layer

# The first layer in a CNN is always a **Convolutional Layer**.

#

#  # ### Convolutional filters

#

#

# A Convolutional Filter much like a **kernel** in image recognition is a small matrix useful for blurring, sharpening, embossing, edge detection, and more.

#

# This is accomplished by means of convolution between a kernel and an image.

#

# The main difference _here_ is that the conv matrices are **learned**.

#

# ### Convolutional filters

#

#

# A Convolutional Filter much like a **kernel** in image recognition is a small matrix useful for blurring, sharpening, embossing, edge detection, and more.

#

# This is accomplished by means of convolution between a kernel and an image.

#

# The main difference _here_ is that the conv matrices are **learned**.

#  # As the filter is sliding, or **convolving**, around the input image, it is multiplying the values in the filter with the original pixel values of the image (aka computing **element wise multiplications**).

#

# As the filter is sliding, or **convolving**, around the input image, it is multiplying the values in the filter with the original pixel values of the image (aka computing **element wise multiplications**).

#  # iNow, we repeat this process for every location on the input volume. (Next step would be moving the filter to the right by 1 unit, then right again by 1, and so on).

# After sliding the filter over all the locations, we are left with an array of numbers usually called an **activation map** or **feature map**.

# ## High Level Perspective

#

# Let’s talk about briefly what this convolution is actually doing from a high level.

# Each of these filters can be thought of as **feature identifiers** (e.g. *straight edges, simple colors, curves*)

#

# iNow, we repeat this process for every location on the input volume. (Next step would be moving the filter to the right by 1 unit, then right again by 1, and so on).

# After sliding the filter over all the locations, we are left with an array of numbers usually called an **activation map** or **feature map**.

# ## High Level Perspective

#

# Let’s talk about briefly what this convolution is actually doing from a high level.

# Each of these filters can be thought of as **feature identifiers** (e.g. *straight edges, simple colors, curves*)

#  # ### Visualisation of the Receptive Field

#

# ### Visualisation of the Receptive Field

#  #

#  #

#  # The value is much lower! This is because there wasn’t anything in the image section that responded to the curve detector filter. Remember, the output of this conv layer is an activation map.

#

# # Going Deeper Through the Network

# Now in a traditional **convolutional neural network** architecture, there are other layers that are interspersed between these conv layers.

#

#

# The value is much lower! This is because there wasn’t anything in the image section that responded to the curve detector filter. Remember, the output of this conv layer is an activation map.

#

# # Going Deeper Through the Network

# Now in a traditional **convolutional neural network** architecture, there are other layers that are interspersed between these conv layers.

#

#  # ## ReLU (Rectified Linear Units) Layer

# After each conv layer, it is convention to apply a *nonlinear layer* (or **activation layer**) immediately afterward.

#

#

# The purpose of this layer is to introduce nonlinearity to a system that basically has just been computing linear operations during the conv layers (just element wise multiplications and summations)

# In the past, nonlinear functions like tanh and sigmoid were used, but researchers found out that **ReLU layers** work far better because the network is able to train a lot faster (because of the computational efficiency) without making a significant difference to the accuracy.

# It also helps to alleviate the **vanishing gradient problem**, which is the issue where the lower layers of the network train very slowly because the gradient decreases exponentially through the layers

# (**very briefly**)

#

# Vanishing gradient problem depends on the choice of the activation function.

#

# Many common activation functions (e.g `sigmoid` or `tanh`) *squash* their input into a very small output range in a very non-linear fashion.

#

# For example, sigmoid maps the real number line onto a "small" range of [0, 1].

# As a result, there are large regions of the input space which are mapped to an extremely small range.

#

# In these regions of the input space, even a large change in the input will produce a small change in the output - hence the **gradient is small**.

# ### ReLu

#

# The **ReLu** function is defined as $f(x) = \max(0, x),$ [2]

#

# A smooth approximation to the rectifier is the *analytic function*: $f(x) = \ln(1 + e^x)$

#

# which is called the **softplus** function.

#

# The derivative of softplus is $f'(x) = e^x / (e^x + 1) = 1 / (1 + e^{-x})$, i.e. the **logistic function**.

#

# [2] [http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~fritz/absps/reluICML.pdf]() by G. E. Hinton

# ## Pooling Layers

# After some ReLU layers, it is customary to apply a **pooling layer** (aka *downsampling layer*).

# In this category, there are also several layer options, with **maxpooling** being the most popular.

# Example of a MaxPooling filter

#

# ## ReLU (Rectified Linear Units) Layer

# After each conv layer, it is convention to apply a *nonlinear layer* (or **activation layer**) immediately afterward.

#

#

# The purpose of this layer is to introduce nonlinearity to a system that basically has just been computing linear operations during the conv layers (just element wise multiplications and summations)

# In the past, nonlinear functions like tanh and sigmoid were used, but researchers found out that **ReLU layers** work far better because the network is able to train a lot faster (because of the computational efficiency) without making a significant difference to the accuracy.

# It also helps to alleviate the **vanishing gradient problem**, which is the issue where the lower layers of the network train very slowly because the gradient decreases exponentially through the layers

# (**very briefly**)

#

# Vanishing gradient problem depends on the choice of the activation function.

#

# Many common activation functions (e.g `sigmoid` or `tanh`) *squash* their input into a very small output range in a very non-linear fashion.

#

# For example, sigmoid maps the real number line onto a "small" range of [0, 1].

# As a result, there are large regions of the input space which are mapped to an extremely small range.

#

# In these regions of the input space, even a large change in the input will produce a small change in the output - hence the **gradient is small**.

# ### ReLu

#

# The **ReLu** function is defined as $f(x) = \max(0, x),$ [2]

#

# A smooth approximation to the rectifier is the *analytic function*: $f(x) = \ln(1 + e^x)$

#

# which is called the **softplus** function.

#

# The derivative of softplus is $f'(x) = e^x / (e^x + 1) = 1 / (1 + e^{-x})$, i.e. the **logistic function**.

#

# [2] [http://www.cs.toronto.edu/~fritz/absps/reluICML.pdf]() by G. E. Hinton

# ## Pooling Layers

# After some ReLU layers, it is customary to apply a **pooling layer** (aka *downsampling layer*).

# In this category, there are also several layer options, with **maxpooling** being the most popular.

# Example of a MaxPooling filter

#  # Other options for pooling layers are average pooling and L2-norm pooling.

# The intuition behind this Pooling layer is that once we know that a specific feature is in the original input volume (there will be a high activation value), its exact location is not as important as its relative location to the other features.

#

# Therefore this layer drastically reduces the spatial dimension (the length and the width but not the depth) of the input volume.

#

# This serves two main purposes: reduce the amount of parameters; controlling overfitting.

# An intuitive explanation for the usefulness of pooling could be explained by an example:

#

# Lets assume that we have a filter that is used for detecting faces. The exact pixel location of the face is less relevant then the fact that there is a face "somewhere at the top"

# ## Dropout Layer

# The **dropout layers** have the very specific function to *drop out* a random set of activations in that layers by setting them to zero in the forward pass. Simple as that.

#

# It allows to avoid *overfitting* but has to be used **only** at training time and **not** at test time.

# ## Fully Connected Layer

# The last layer, however, is an important one, namely the **Fully Connected Layer**.

# Basically, a FC layer looks at what high level features most strongly correlate to a particular class and has particular weights so that when you compute the products between the weights and the previous layer, you get the correct probabilities for the different classes.

#

# Other options for pooling layers are average pooling and L2-norm pooling.

# The intuition behind this Pooling layer is that once we know that a specific feature is in the original input volume (there will be a high activation value), its exact location is not as important as its relative location to the other features.

#

# Therefore this layer drastically reduces the spatial dimension (the length and the width but not the depth) of the input volume.

#

# This serves two main purposes: reduce the amount of parameters; controlling overfitting.

# An intuitive explanation for the usefulness of pooling could be explained by an example:

#

# Lets assume that we have a filter that is used for detecting faces. The exact pixel location of the face is less relevant then the fact that there is a face "somewhere at the top"

# ## Dropout Layer

# The **dropout layers** have the very specific function to *drop out* a random set of activations in that layers by setting them to zero in the forward pass. Simple as that.

#

# It allows to avoid *overfitting* but has to be used **only** at training time and **not** at test time.

# ## Fully Connected Layer

# The last layer, however, is an important one, namely the **Fully Connected Layer**.

# Basically, a FC layer looks at what high level features most strongly correlate to a particular class and has particular weights so that when you compute the products between the weights and the previous layer, you get the correct probabilities for the different classes.

#  # # CNN in Keras

# **Keras** supports:

#

# - 1D Convolutional Layers;

# - 2D Convolutional Layers;

# - 3D Convolutional Layers;

#

# The corresponding `keras` package is `keras.layers.convolutional`

# #### Convolution1D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution1D

# Convolution1D(nb_filter, filter_length, init='uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample_length=1,

# W_regularizer=None, b_regularizer=None,

# activity_regularizer=None, W_constraint=None,

# b_constraint=None, bias=True, input_dim=None,

# input_length=None)

# ```

# >Convolution operator for filtering neighborhoods of **one-dimensional inputs**. When using this layer as the first layer in a model, either provide the keyword argument `input_dim` (int, e.g. 128 for sequences of 128-dimensional vectors), or `input_shape` (tuple of integers, e.g. (10, 128) for sequences of 10 vectors of 128-dimensional vectors).

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a convolution 1d of length 3 to a sequence with 10 timesteps,

# # with 64 output filters

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution1D(64, 3, border_mode='same', input_shape=(10, 32)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 64)

#

# # add a new conv1d on top

# model.add(Convolution1D(32, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 32)

# ```

# #### Convolution2D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution2D

# Convolution2D(nb_filter, nb_row, nb_col,

# init='glorot_uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample=(1, 1),

# dim_ordering='default', W_regularizer=None,

# b_regularizer=None, activity_regularizer=None,

# W_constraint=None, b_constraint=None,

# bias=True)

# ```

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a 3x3 convolution with 64 output filters on a 256x256 image:

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution2D(64, 3, 3, border_mode='same',

# input_shape=(3, 256, 256)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 64, 256, 256)

#

# # add a 3x3 convolution on top, with 32 output filters:

# model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 32, 256, 256)

#

# ```

# ## Dimensions of Conv filters in Keras

# The complex structure of ConvNets *may* lead to a representation that is challenging to understand.

# Of course, the dimensions vary according to the dimension of the Convolutional filters (e.g. 1D, 2D)

# ### Convolution1D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `steps`, `input_dim`).

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `new_steps`, `nb_filter`).

# ### Convolution2D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `channels`, `rows`, `cols`) if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `rows`, `cols`, `channels`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `nb_filter`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`)

# if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`, `nb_filter`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

# # CNN in Keras

# **Keras** supports:

#

# - 1D Convolutional Layers;

# - 2D Convolutional Layers;

# - 3D Convolutional Layers;

#

# The corresponding `keras` package is `keras.layers.convolutional`

# #### Convolution1D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution1D

# Convolution1D(nb_filter, filter_length, init='uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample_length=1,

# W_regularizer=None, b_regularizer=None,

# activity_regularizer=None, W_constraint=None,

# b_constraint=None, bias=True, input_dim=None,

# input_length=None)

# ```

# >Convolution operator for filtering neighborhoods of **one-dimensional inputs**. When using this layer as the first layer in a model, either provide the keyword argument `input_dim` (int, e.g. 128 for sequences of 128-dimensional vectors), or `input_shape` (tuple of integers, e.g. (10, 128) for sequences of 10 vectors of 128-dimensional vectors).

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a convolution 1d of length 3 to a sequence with 10 timesteps,

# # with 64 output filters

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution1D(64, 3, border_mode='same', input_shape=(10, 32)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 64)

#

# # add a new conv1d on top

# model.add(Convolution1D(32, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 10, 32)

# ```

# #### Convolution2D

#

# ```python

# from keras.layers.convolutional import Convolution2D

# Convolution2D(nb_filter, nb_row, nb_col,

# init='glorot_uniform',

# activation='linear', weights=None,

# border_mode='valid', subsample=(1, 1),

# dim_ordering='default', W_regularizer=None,

# b_regularizer=None, activity_regularizer=None,

# W_constraint=None, b_constraint=None,

# bias=True)

# ```

# #### Example

#

# ```python

#

# # apply a 3x3 convolution with 64 output filters on a 256x256 image:

# model = Sequential()

# model.add(Convolution2D(64, 3, 3, border_mode='same',

# input_shape=(3, 256, 256)))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 64, 256, 256)

#

# # add a 3x3 convolution on top, with 32 output filters:

# model.add(Convolution2D(32, 3, 3, border_mode='same'))

# # now model.output_shape == (None, 32, 256, 256)

#

# ```

# ## Dimensions of Conv filters in Keras

# The complex structure of ConvNets *may* lead to a representation that is challenging to understand.

# Of course, the dimensions vary according to the dimension of the Convolutional filters (e.g. 1D, 2D)

# ### Convolution1D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `steps`, `input_dim`).

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **3D** tensor with shape: (`samples`, `new_steps`, `nb_filter`).

# ### Convolution2D

#

# **Input Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `channels`, `rows`, `cols`) if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `rows`, `cols`, `channels`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`

#

# **Output Shape**:

#

# **4D** tensor with shape:

#

# - (`samples`, `nb_filter`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`)

# if `dim_ordering='th'`

# - (`samples`, `new_rows`, `new_cols`, `nb_filter`) if `dim_ordering='tf'`