#

The Newton-Euler equations

#

# The

Newton-Euler equations are a formalism to describe the combined translational and rotational dynamics of a rigid body.

# For a two-dimensional (at the $xy$ plane) movement, their general form are given by:

#

# $$ \sum \mathbf{F} = m \mathbf{\ddot{r}}_{cm} $$

#

# $$ \sum \mathbf{T}_z = I_{cm} \mathbf{\ddot{\alpha}}_z $$

#

# Where the movement is considered around the center of mass ($cm$) of the body, $\mathbf{F}$ and $\mathbf{T}$ are, respectively, the forces and torques acting on the body, $\mathbf{\ddot{r}}$ and $\mathbf{\ddot{\alpha}}$ are, respectively, the linear and angular accelerations, and $I$ is the body moment of inertia around the $z$ axis passing through the body center of mass.

# It can be convenient to describe the rotation of the body around other point than the center of mass. In such cases, we express the moment of inertia around a reference point $o$ instead of around the body center of mass and we will have an additional term to the equation for the torque:

#

# $$ \sum \mathbf{T}_{z,O} = I_{o} \mathbf{\ddot{\alpha}}_z + \mathbf{r}_{cm,o}\times m \mathbf{\ddot{r}}_o $$

#

# Where $\mathbf{r}_{cm,o}$ is the position vector of the center of mass in relation to the reference point $o$ and $\mathbf{\ddot{r}}_o$ is the linear acceleration of this reference point.

#

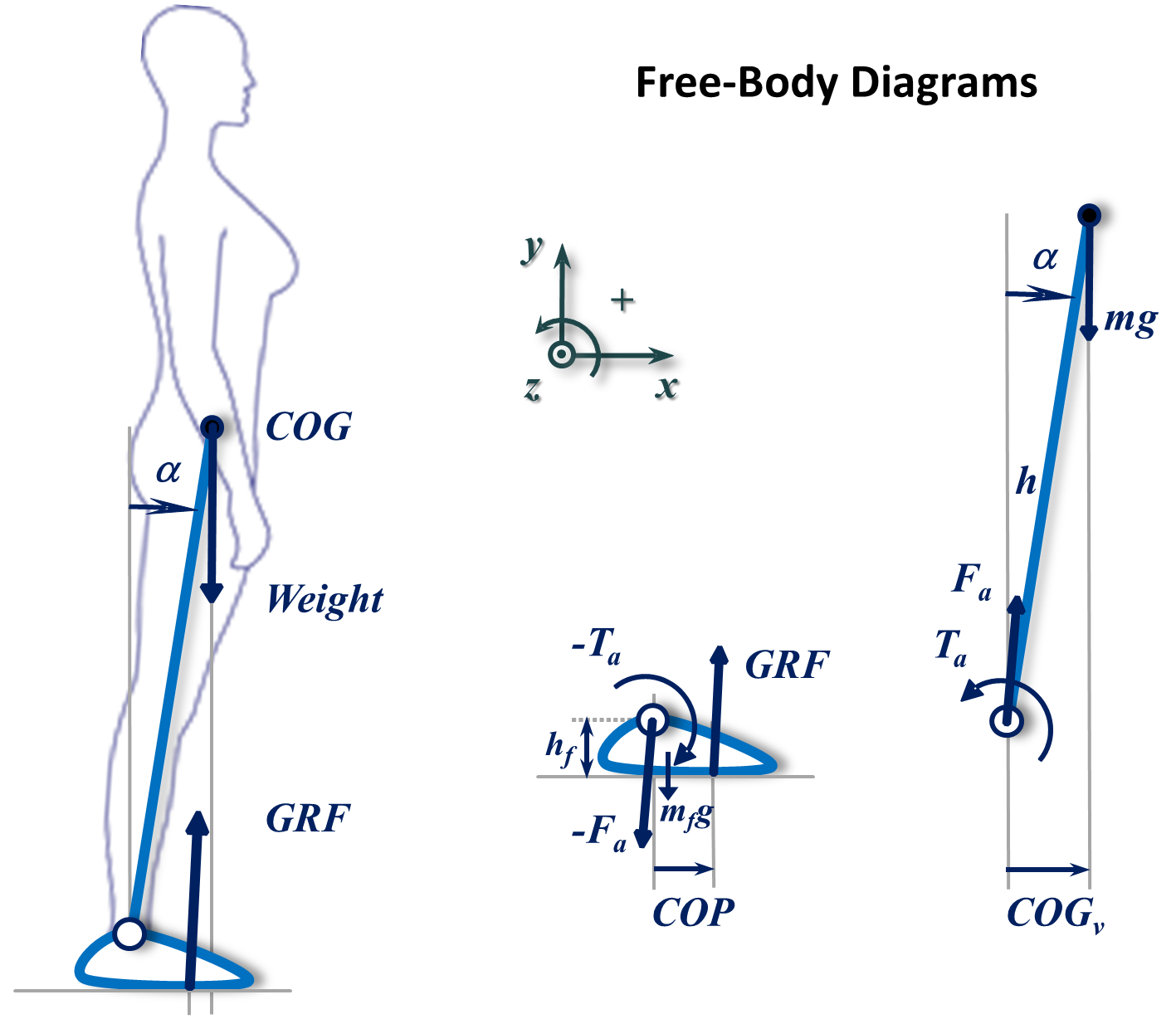

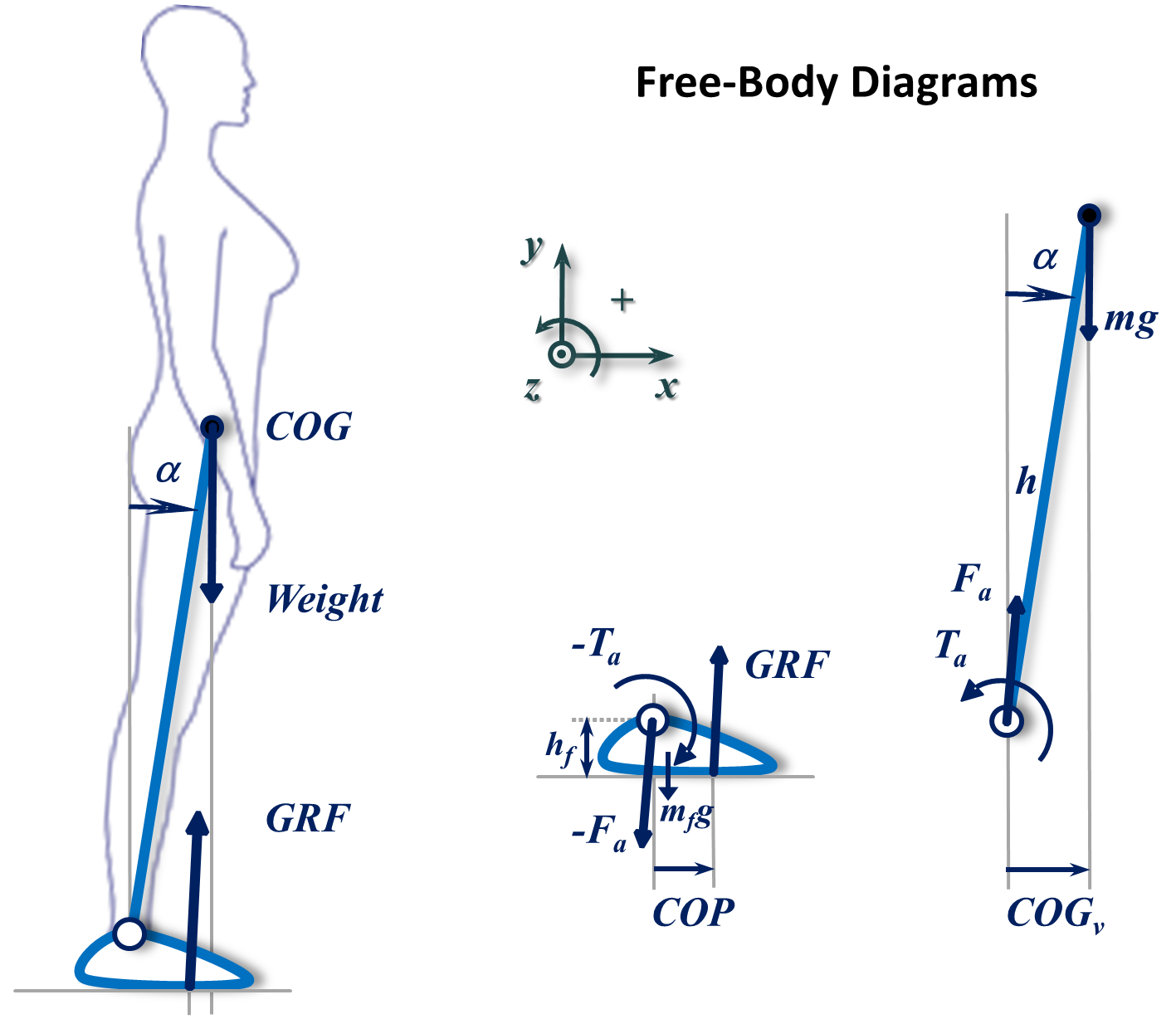

See this notebook about free-body diagram.

#

#

The Fourier transform

# The

Fourier transform is a mathematical operation to transform a signal which is function of time, $g(t)$, into a signal which is function of frequency, $G(f)$, and it is defined by:

#

# $$ \mathcal{F}[g(t)] = G(f) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} g(t) e^{-i2\pi ft} dt $$

#

# Its inverse operation is:

#

# $$ \mathcal{F}^{-1}[G(f)] = g(t) = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} G(f) e^{i2\pi ft} df $$

#

# The function $G(f)$ is the representation in the frequency domain of the time-domain signal, $g(t)$, and vice-versa. The functions $g(t)$ and $G(f)$ are referred to as a Fourier integral pair, or Fourier transform pair, or simply the Fourier pair.

#

See here for an introduction to Fourier transform and

see here for the use of Fourier transform to solve differential equations.

#